I have loved board gaming since I was a young kid. Set up the board, draw cards, roll the dice, let's go! I especially love games that simulate historical events. These are games where the theme is paramount. Nobody would claim that Monopoly is a simulation of the real estate business. History, on the other hand, and military history especially, are ripe for games that are fun to play AND give you a sense of what the real event might have been like. The role-playing aspect of these board games is my sweet spot.

Historicity

OK, I get it, a historical game should play historically, but this is a tricky balance. Too far in one direction and the history becomes just a façade draped over the game (a battlefield version of Monopoly). In the other direction, it becomes a tight script that forces you down a predetermined path.

Can I Replicate History?

This is not as easy as you would think. It requires a lot of work on the designer's part to storyboard the event, recording who did what, when, and where. Then they have to figure out where the game might historically deviate from that path. I do not want this to be tightly scripted. I want the game to play differently in each session, but I don't want to see outcomes that just were not possible.

In the Battle of the Bulge, the Germans launched a last-ditch offensive aimed at Antwerp in order to split the western Allies in the hopes that they would sue for peace. In the real event, the Germans barely made it to their initial objective, the Meuse River, and by then it was clear this wasn't going to work out for them. True, there was a fair amount of bad luck and ineptitude that hindered them, but even if they did everything right, there is no way they would have made it to Antwerp short of Allied capitulation. If anything, the range of likely outcomes may skew worse than historical. A large number of games on this topic just don't work for me because the designers have implemented German supermen, much more powerful than their historical counterparts. I know why they did this: A game in which the Germans have a decent chance of winning makes for a more popular product. They're just not the ones I'd want to play.

Am I Playing the History or Playing the Game?

Hopefully, the Venn diagram of what the historical actor would do and what the player can do has significant overlap. Even if the game gives you a believable outcome, all too frequently what you had to do to get there is not historical. This is usually the result of a mismatch between a game mechanic and what it is intended to simulate.

A common mistake is to conflate fighting with firing. The former describes what two sets of people are doing to each other. If someone is fighting you, it makes sense that the more people you've got fighting on your side, the better you'll do. Firing, on the other hand, describes what one set of people is doing TO another. If you're being fired upon, adding more people to your side just increases the number of targets. Despite this, there are a number of games out there that, because they use an odds-based mechanic to resolve fire, adding more targets means less damage. The strategy and tactics you use to win the game should be recognizable by the historical actors as viable approaches.

Ergonomics

A board game is a machine like a car or accounting software. It takes inputs, processes them, and provides outputs. The human is an integral part of this machine. They do the thinking and move the pieces around, regulated only by the game's physical components, the other humans involved, and past experience. This can be a tough interface to design for and, frequently, leads me to ditch what would otherwise be a good game.

While the human brain is a powerful tool, it has its limits. Let's only use it when and where it really matters. When evaluating this criterion, it helps to think of types of tasks:

- Intuitive – These are tasks that should not require conscious thought, like determining which pieces are yours.

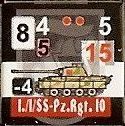

- At a Glance – This is an explicit action on the player's part, but with minimal effort. It's the barrage phase, which of my units are artillery?

- Hands-On – Detailed effort that requires interaction with multiple parts of the game. Let's resolve this combat.

Is the Graphic Design Useful?

The data, art, and how those two are presented make up a game's graphic design. This serves three purposes: deliver information, look cool, and sell games. Game publishers clearly need to sell games. Unfortunately, that frequently leads to designs that make for great marketing materials but impede the game's ability to deliver information. It doesn't help that most gamers seem to value the ludic quality of a design over its usefulness.

Supply is something that's frequently a major factor in the kind of games I like. Usually, there's a point in each turn where you check the supply status of your units. By then, however, it's too late to do anything if you find some units out of supply. Since roads are key to delivering supplies, make those features obvious on the map so that the positioning of your units for supply is more intuitive. This has an added benefit when you are checking supply: you don't have to have to examine every unit on the map. At a glance, you would know the status for most of your units; therefore, only getting hands-on for that problematic subset.

Is the Physical Design Helpful?

While the graphic design speaks to the quality of the components that exist, that still leaves unanswered the question of whether the right components were produced in the first place. Do the game board (map in wargame parlance), pieces, and rule book allow for optimal physical interaction? Do you need additional information, like charts and tables, in order to efficiently play the game? Can you position the components for easy access? Some games have a big footprint. I'm not opposed to that, just the opposite, I love large games. I don't like games that are inefficient in their use of space.

Combat resolution can be a convoluted process. The following case is typical:

- Select the target – Hopefully, this is no more than an at-a-glance effort unless there are a small number of possibilities.

- Select attacking units – You'll likely NOT want to attack with everyone adjacent to the target. Some of your units might be too vulnerable or you want to save them for different combat this turn. Unless, of course, the rules require that you attack with everyone. Lots of decisions to make.

- Calculate defending combat value – Time for some math. Add up all of the combat values for the target units. You may also have to multiply/divide based on the state of those units and the terrain they occupy.

- Calculate attacking combat value – Ditto what you just did for the defenders. Now you're holding two numbers in your head.

- Calculate odds – Some more math (you're not playing these games if you don't like math). Divide the larger by the smaller so you get a ratio of attacker to defender.

- Find the appropriate odds column on the combat table – Rarely will your result match up to one on the combat table. If you arrive at 2.95:1, most games will have you round that down to 2:1, some up to 3:1. Oh, and you may adjust the column left or right depending on the context of this combat.

- Roll the die and modify – AGAIN, you may have to apply modifiers based on yet more factors.

- Determine results – Cross-index the modified die roll with the column on the combat table to determine the result of just this one combat.

- Apply results – You'd think your work is done now, but you need to apply casualties, perhaps units of one side need to retreat (these rules can be complicated in order to prevent the player from gaming the system to turn a retreat into an advance). Then, as the attacker, if the target space has been emptied, sometimes you can enter or even move past it.

I go into this detail in order to convey that there's a lot of moving parts here. Your brain is storing data, remembering rules, consulting tables of information, and all the while making value judgments. This will likely be painful the first few times you do this in a game. If it continues to be so, that's a sign of a poor design.

Fun

After all that talk of math, you're probably wondering where the fun is. I can't blame you. Some of these games feel more like work than play. There is a distinct threshold for me, though, where these games clearly are fun. If the above doesn't trip me up, these next two factors will turn me into a fan.

Are There Real Decisions to Make?

Do I go with Option A or Option B? This is not a real decision if Option B never makes sense. Sometimes, when you're first playing a game, A vs. B is a tough call, but after a few plays, you learn the conditions under which one or the other makes sense. Then it's no longer a real decision. You can go too far the other way, too. When it's too difficult to calculate which option makes sense, it's no different than flipping a coin. I want it just hard enough to engage my brain, but not paralyze me.

Landing on a property in Monopoly, you almost always buy it. The cases when you shouldn't are pretty clear. I crave situations that make me think hard and take clear risks. Do I strip units from my left flank in order to deliver an overwhelming attack from my right? Hmmm, that's a tough call. Worst case scenario, I not just lose the battle, I could lose the war. However, my forces are slightly more mobile than my opponent's. And I know my opponent, his play tends towards the conservative. I'm going for it!

Did the Game Tell a Story?

So you just finished a game. Do you immediately put it away and talk about what you want to play next? That's not a good sign. A good game will have me kibitzing afterward. I see games as not much different than a book or a movie. The good ones will tell you a story. A great session will stick in your memory for years. These games will have me jonesing for more: more sessions with this game, more games on this topic or using this system, and, of course, more books so I can get smarter on the topic. That's how I win a game.

I Don't Care

I'm not overly anal about these games. There are facets of gaming that are very important to other players but don't factor into my thinking.

Victory Conditions

I have problems with the concept of victory conditions as a special case of my Playing the History vs. Playing the Game concern, but they've never kept me from playing a game. My issue is that most designers (and players, for that matter) conflate victory in the game with a victory in the event being portrayed. There is a lot of overlap in the Venn diagram of the two, but where they don't, trying to satisfy the victory conditions of the game leads you to behave in ahistorical ways.

The problem is that victory conditions for a game are developed based on the historical outcome. The moment you start the game, however, you are branching history into an alternate reality. Historically, Little Round Top was an important terrain feature in the Battle of Gettysburg and most games award the player victory points for its possession. It was important because it anchored the left-wing of the Union Army. But what if in your game, your flank is resting elsewhere?

Another issue is, victory for whom? In the Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg example, is it for the army itself (morale increased), for General Meade (I get to keep my job), Lincoln (my political options have opened up), or the people of the northern states (preserving the union is worth the sacrifice). So many factors go into making this judgment, as well as the time necessary to process those factors, that developing an objective formula for calculating victory is nigh impossible.

Part of the post-game kibitzing I enjoy so much is talking through what just happened. To me, THIS is the way to figure out victory: both players talking it through and coming to a consensus. Usually, I performed poorly and should never be given a battlefield command.

Balance

This flows from the victory conditions. Most players want a game where both sides have a roughly equal chance to win. For me, however, assuming the historicity passes muster, I'm OK with an out-of-balance subject. Some struggles were just not even. Consider the German invasion of Poland in 1939. The Poles will never win that war militarily. At best, they could make it a slog of the Germans, inflicting high casualties. Perhaps the Poles can win diplomatically by getting another power to intervene, but that can be a double-edged sword, as they learned in the real-life event. All the possible outcomes in which the Poles might conceivably claim a moral victory have got to be way outnumbered by the likelihood of utter defeat and ruin.

Some designers will address these imbalanced situations with victory conditions that call for the player to perform better than their historical counterparts. This leads to ahistorical behavior. You become concerned with holding out longer or taking fewer casualties, but historically, was that really what you were trying to achieve? Winning can mean more than the Clauswitzian ability to impose your will on the enemy.

I Like What I Like

I think this is as close as I can get to codifying what I like in a game. It's not perfect, but close enough. Give me believable history in an ergonomic package and I'll buy your game.

Of Possible Interest

- Redmond A. Simonsen

- Historical background

- The Right Way to Play Monopoly