My Beef with Odds-Based Combat Resolution

Combat resolution defines a war game. It shapes whether battles feel plausible or ridiculous, whether luck feels thrilling or frustrating, and whether players make historically grounded decisions or not. When a system's foundation is shaky, even the best map, OOB, and scenario design can't save the experience. Odds-based combat, in my view, starts with the wrong foundation. Using a single random roll to cover every possible factor, from weapon effectiveness to morale breakdowns to pure dumb luck wildly oversimplifies something that, in reality, is a messy, chaotic, and multi-layered process.

Combat isn't one thing; it's multiple overlapping questions resolving at once:

-

What is the maximum kinetic energy the attacking units can project onto the enemy?

How many bullets, shells, bayonets, and stern looks can they deliver under perfect conditions?

-

What is the probability curve across that range?

Maybe 100 steps between 0% and 100%, but weighted based on conditions — not a flat line.

-

What is the actual amount delivered?

A random pull from the curve above.

-

What is the actual effect on the target?

Casualties, broken radios, abandoned tanks, shattered morale — again, random, and again influenced by context.

And then, of course, the same four steps happen for the other side.

We need abstraction for a playable game — no question — but collapsing all this into a single random number based on a ratio feels wrong to me. Odds-based combat can sometimes approximate reasonable outcomes, but it fails badly at the edges — and, worse, it subtly warps the way players think about real-world combat.

The Odds-Based Approach to Combat Resolution

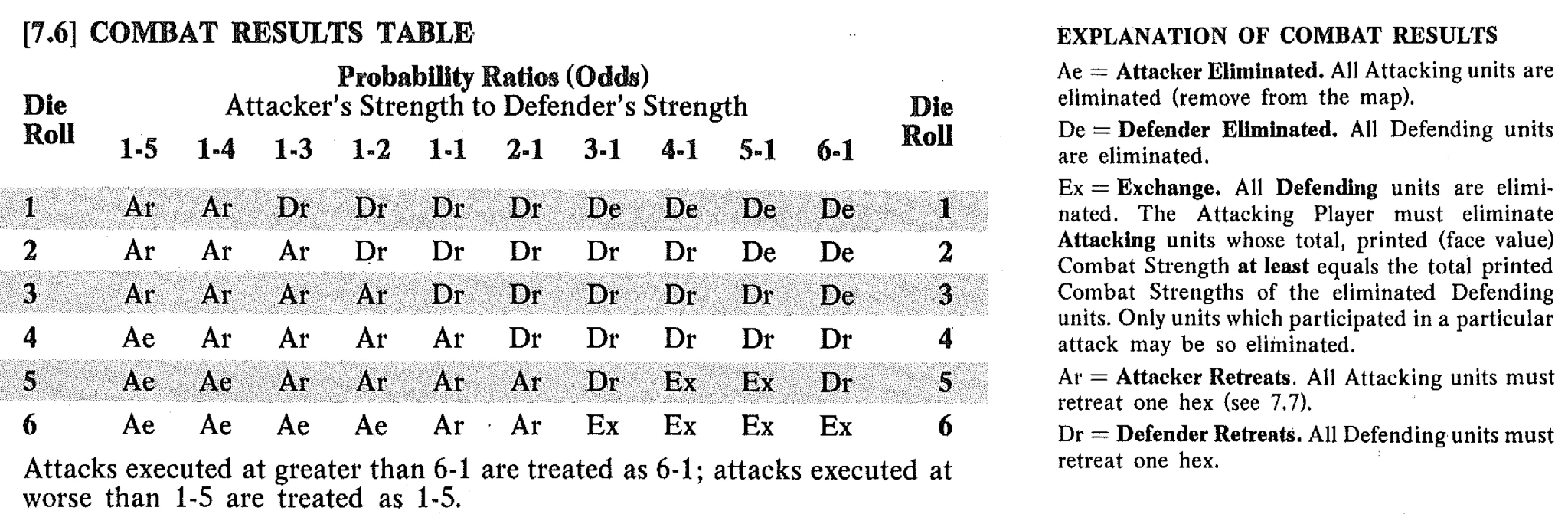

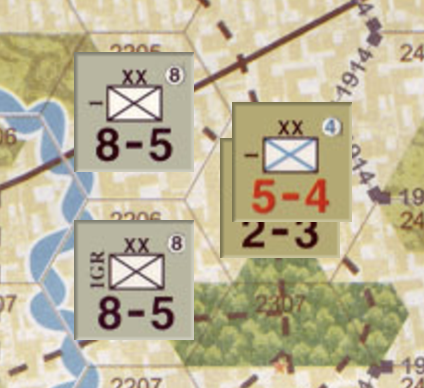

Most war games resolve combat by adding up the attacker's strength, comparing it to the defender's, and turning that into an odds ratio. It's simple, familiar, and quick. Let's take a look at an example from the Chickamauga scenario of SPI's Blue & Gray game:

In this attack, the odds are 16 Rebel strength to 5 US, which would use the 3:1 odds column on the Combat Results Table (CRT). (16:5 = 3.2:1, round down)

The possible results from a six-sided die roll:

- 1 : Eliminate the US brigade.

- 2-5 : The US brigade retreats.

- 6 : Eliminate the US brigade and eliminate a number of Rebel brigades with a total strength of at least 5, which means you must eliminate 2 brigades.

Do some math, find the appropriate column, roll 1d6, apply the results. Next combat! What could be wrong with this approach?

The Problems with Odds-Based Combat

Well, I see plenty wrong here.

-

It Conflates the Ability to Deal Damage with the Ability to Absorb It

Combat boils down to four separate random processes: how much force each side can unleash, and how much each side can absorb. Odds-based systems jam these into a single dimension.

When you calculated the 3:1 ratio above, what exactly is being measured? Quantity of troops? Their quality? How they are armed? How well protected they are? The ratio tries to do too much with a single number — and that's why we frequently end up needing a pile of modifiers to fix obvious contradictions.

Imagine a WW2 light tank unit, crewed by the best tankers in history, attacking a unit of heavy tanks with green crews. The light tanks might dodge well, flank smartly, and cause temporary chaos — but their guns can't seriously harm heavy armor. Conversely, even a clumsy heavy tank unit can wreck light tanks when they get a hit. How does an odds ratio capture that?

-

It Offers Too Few Possible Outcomes

Typical CRTs are based on 1d6, 2d6, or 1d10 rolls — six, eleven or ten outcomes. That's not nearly enough to model real-world variance. Even if we assume two possible results (good or bad) for each of the four random processes I outlined earlier, that's 16 combinations. If you have six possible results per process, that's 1,296 combinations.

More possible outcomes mean long tails, freak events, marginal victories, and no effect results — all of which happen constantly in real battles. It also means you can loosen up the effect on Side A from the effect on Side B, rather than tightly binding them together in a zero-sum dance.

-

It Does Not Distinguish between Large and Small Combats

Whether it's 16:5, 7:2, or even 300:100, the typical odds-based approach treats them the same. This system conflates the relative number of casualties with the absolute number of casualties. Yes, as you add more units to a battle, the number of casualties on both sides will increase, but the likelihood that your side will be completely eliminated decreases.

Some games have multiple CRTs which are used based on the size of the battle. I think this is a reasonable approach to bring odds-based combat closer to a realistic model, but it's yet another modifier to fix the system's obvious contradictions.

-

It Misinterprets the 3:1 Rule

Odds-based combat systems likely owe their existence to military science's 3:1 rule — the idea that attackers need a 3:1 advantage to have a good chance of success. But that rule is about absorbing the enemy's fire as much as it is about delivering your own. You don't automatically win just because you have 3x the numbers; you are more likely to win because you can lose 2x as much and still keep going. Odds-based combat forgets that subtlety and treats force ratios as a magic key to victory.

The 3:1 Rule is about quantity, but the strength points that are used to calculate the odds represent more than that. Clearly 100 well-trained soldiers are going to perform better than 100 conscripts quickly thrown into battle. But how much better trained does the former force have to be in order to get to 2:1 odds? I think that's an unanswerable question.

-

More Means Better, Sometimes

Increasing your strength in a fight seems like a reasonable approach. From the example above, if the Rebels had 12 strength points to the US's 5, that would be 2.4:1, rounding down to 2:1. If the Rebel player could commit one more unit with at least 3 strength points to that fight, the odds would increase to 3:1, but if they could only find a unit with 2 strength, nothing changes. Players, then, are constantly on the lookout for additional units with just the right amount of strength. This, however, warps the game's incentives in a non-historical manner.

War games have some elements of role-playing games in that what the players are doing should mirror, to a certain extent, what the historical actors would be doing in the same situation. Given that, what does it mean after you've completed the movement of some of your units and totalled up the strength only to realize you're 1 point short of the next odds column? Even if the historical actor believes just one more batch of soldiers is enough to tilt the balance, finding them would take time. The effect, then, of looking for that additional strength is to stop time while the message is delivered to the extra unit and it marches over to participate in the battle. And this assumes the historical actor knows precisely the combat value of the involved units. This just doesn't ring true.

-

The Pull of Tradition

In the end, I think odds-based systems stuck around because they're easy to design, easy to teach, and players have been trained to expect them. They're the standard — but just because something is standard doesn't mean it's good.

If we want war games that feel richer, more unpredictable, and closer to the real-world chaos they're meant to model, we need to think beyond simple odds.

Other Approaches to Combat Resolution

Odds-based combat resolution is the most common system in war gaming, but there are other options.

Roll to Hit

This is an approach that, instead of using a combat results table, has the players rolling a number of dice based on their units' combat strength, then examining the results to determine how much damage is inflicted upon the opponent. There's more decision making in this process, but it can involve rolling buckets of dice. Here is an example from War of 1812 from Columbia Games.

In this attack, the Americans, as the defenders, can choose to stay and fight or retreat. If they fight, they roll six dice. For each result of 6, the British forces take a hit. Then the British player chooses to retreat or fight. This continues until one side is eliminated or retreats. Retreating is painful because your opponent gets one last shot, scoring hits on a result of 4 or more!

I like this approach because it presents the players with the fight-or-flight decision. Unlike with odds-based combat, if things are going bad, you have the option to risk a retreat in the hopes that you'll have some strength remaining after the fight. This system also addresses many of the problems with the odds-based approach.

In this fight, 8 British strength points are going up against 6 American. This means there's up to 56 possible outcomes with both sides ranging from no losses to utter destruction for one side. Roughly double that to factor in the possibility of a retreat.

This approach, though, does have its limitations. Combats take much longer to resolve, so it limits the size of the conflicts the system can simulate ( Please, no fights of 300 to 100! ). Also, the only attributes involved are the combat value of the units involved and the die value that results in a hit. This does not give the system much room to deal with variations among the units. This is fine if both sides are somewhat similar in quality and armaments. The more those two factors vary, though, the less useful this approach becomes.

Fire Combat

This is an approach where, as the name spells out, one or both sides fire at the other. While similar to the Roll to Hit approach, this system uses a single roll that the player cross-indexes on a column of a fire table to determine the result inflicted upon their opponent. This is used in most, if not all, tactical level games where the units can deliver kinetic energy at distances beyond the adjacent space. However, this is also used in situations at a larger scale. This is an example from Tannenberg: Eagles in the East by Schroeder Publishing & Wargames.

The Germans, as the attacker, roll first with 16 strength points to determine the number of hits dealt to the Russian force. Then, the Russian player must decide whether to stand or retreat. The former allows them to make a roll using triple their strength (this is World War 1 after all), while the later option doubles their strength for the return shot, but requires the Russians to retreat.

Fire Combat allows for more complexity than the Roll to Hit approach. What I didn't note above is how terrain and supply factor into the outcome. Also, some things are decisions for the players, while others are mandates. There are too many permutations to spell out here. This complexity allows the game to model greater differences than the Roll to Hit approach while also taking less time to resolve.

Of all the extant combat resolution processes, this is my favorite. Yet, I still find it lacking. You can factor in armaments and protection, but the quality of the troops involved is still abstracted. In game terms, the typical German infantry division is 60% larger than the Russian. Yet, in real life, the Russian division had more soldiers. The German division was better armed than its Russian counterpart, true, but it was also better trained and, frequently, better motivated. Much of the difference in strength is a result of this difference in quality. I don't think this is wrong, necessarily. Rather, I would like to see quality treated more explicitly in the combat resolution process.

A New Way of Thinking about Combat Resolution

I believe Fire Combat can be the basis for a realistic model, but it needs supplementing.

Quality First

"In war, the moral is to the physical as three is to one."

Quality — or morale, discipline, cohesion, whatever term you prefer — is the attribute that best captures how well a unit is likely to perform in combat. It's a composite of many factors: some fluctuate rapidly, like fatigue or supply, while others shift more gradually, like training or leadership. Some of these factors are subjective, such as motivation; others are quantifiable, like ammunition levels. Taken together, they represent a unit's readiness and resilience under fire.

I would argue that quality is the single most important determinant of combat performance. It should be the primary factor in resolving combat outcomes. Yet, most games either ignore it entirely or bury it within a generalized combat strength value. Even in games that do model quality explicitly, it's often used reactively — a morale check after a loss — rather than proactively, to shape the flow of battle. That's a missed opportunity. A unit's quality affects not just how it responds to setbacks, but how it executes its mission from the start.

Do You Have Your Sh!t Together?

Before dice hit the table, there's a more fundamental question to ask of each unit: are they in fighting shape? The many factors that define a quality rating combine into a single judgment: can this unit execute its orders under stress? While this could be modeled with shades of gray, a simple yes/no morale check captures the essential friction of warfare without bogging down play.

Here's the basic idea: both attacker and defender make a morale check before combat is resolved. This determines not just how well they fight, but whether they get to fight at all, and how the resolution process unfolds. You then cross-index the results to determine the outcome flow:

| Attacker PASSES | Attacker FAILS | |

|---|---|---|

| Defender PASSES | This is a standup fight, both sides are going to take hits. | The attack is repulsed with heavy casualties. |

| Defender FAILS | The defender takes a beating and flees the field. | No effect. We thought there would be combat, but neither side had it together. |

If you use this to build on the Fire Combat model, you would retain that approach's benefits while dramatically increasing the range of possible outcomes. It introduces psychological dynamics and command friction into the heart of resolution, which are often glossed over in traditional systems. And crucially, it makes morale a primary factor in combat — just as it is in real life. Units that fail their check don't just fight worse — they may not fight at all.

Further Considerations when Building a Combat Resolution Model

There is no clear boundary between fighting and the other actions units may take on the battlefield. Here are some additional considerations that should factor into the overall process of resolving combat:

-

What are the results of combat?

Reduced ability to project violence on the enemy, yes, but how and why? Reduced numbers of troops might cause that when they are all similarly armed. In more modern armies, though, it's about the loss of heavy weapons like machine guns. More than this is that while untouched by physical harm, if enough individuals are affected mentally, they may be temporarily hors de combat. Then there's the question of who has control of the contested ground after the fight? How should all of this factor into combat resolution and the ability to regain such losses if they are only temporary?

-

What is the time cost of fighting?

In all games, units pay a time cost when moving by spending movement points. Only some games impose such a cost on combat for the attacker. The defender is never forced to pay that cost. In a typical game, you could have the first player move a unit to its full capacity and then engage in combat. The defending unit, even if forced to retreat, when it's the second player's turn, is now able to move to its full capacity and engage in combat. How is this possible? That unit just engaged in combat with a unit that just ran out the clock on its turn. Does time rewind? Doesn't this give the second player the benefit of knowing what happens in future, allowing them to act accordingly?

-

Where is the line between fighting and moving?

Combat is movement. The attacking units are moving, or attempting to move, into the defender's hex. The defender may be forced to move out of the hex depending upon the results. This is clearly combat, but what about when the unit moves within range of the enemy? Tactical games allow for defensive or opportunity fire in such cases.

When you zoom out to a larger scale, the rules usually call for a zone of control. But what is a zone of control other than the unit projecting its violence such that the enemy needs to adjust how it moves? Movement, in this case, is combat. Shouldn't it be treated as such? Certainly not in an as extensive manner as regular combat, but there should be the threat of losses and denial of that ground to the moving unit.

Let's Fight Smarter

The odds-based system persists because it's easy to implement and familiar to players. But familiarity shouldn't be a defense for flawed mechanics. If we want war games that better model real combat — with all its chaos, complexity, and uneven human factors — we need to think beyond strength ratios and single die rolls. By making unit quality and cohesion central to resolution, designers can capture nuance without sacrificing playability. It's time to retire combat models that flatten everything into a ratio and start building systems that reflect how fights really unfold — not just who had the bigger stack.

Further Reading

- Here's a journal article that examines and finds wanting the 3:1 rule. It's from a Korean institution, but written (mostly) in English: The 3:1 Rule: A Viable Tool?

- The history:

-

The gaming:

- Chickamauga: The Last Victory, 20 September 1863 by SPI Games.

- War of 1812 by Columbia Games

- Tannenberg: Eagles in the East by Schroeder Publishing & Wargames